I had a couple of hours to kill today, and used them to meander around Fremantle, which is Perth’s port. It’s long been one of my favourite (urban) places in Western Australia, and would certainly take several visits to explore thoroughly. In this blog, I mention only some of them …

One of the delights of wandering around Freo (as it is often known by the locals – Australians are notoriously prone to short handing names!) is the built environment. Although it dates only from the early part of the nineteenth century, the architecture often seems ‘old’ by local standards and many buildings have been lovingly renovated recently. The main impetus for the renovations was the America’s Cup yacht race, which was based in Freo in 1986. The images above show some examples, ranging over at least a century. Many fine buildings show some of the affluence of the port years ago, while others show the early influences of convict labour. (Western Australia was founded as a British penal colony in 1829.) A stroll around Freo will delight anyone interested in Victorian-era and early 20th century streetscapes.

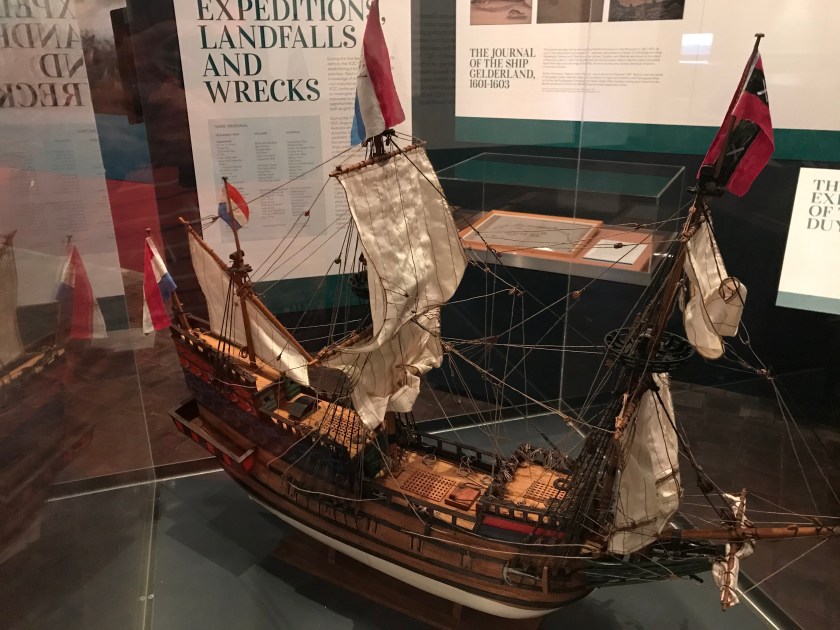

I also popped in to the lovely Shipwrecks Museum, a museum constructed and maintained by the state government, focusing on the many maritime adventures associated with early Western Australia. It’s a lovely museum with many aspects of the maritime world on display, and so it’s very easy to spend an hour or two there. Pride of place in the museum is a gallery housing some recovered parts of the Batavia, a vessel owned by the Dutch East Indies Company, which sank on Western Australia’s coast in the 17th century:

The first image shows a scale model of the Batavia, while the second shows a large part of the reconstruction. The ship sank in 1629 (a full two hundred years before the penal colony was founded), with details of the events still being found; a mutiny was involved, some evil events too place (murdering of men, women and children) and ultimately some ringleaders were executed. The ship sank en route to Batavia (the same name as the ship, but is a city today called Jakarta, in today’s Indonesia), and senior crew went there and back to get help. This area of the world was frequently encountered by the Dutch, as it was not far from the route from the bottom of Africa to the Dutch East Indies (known as Indonesia today), a major source of spices for Europe and wealth for the private company VOC.

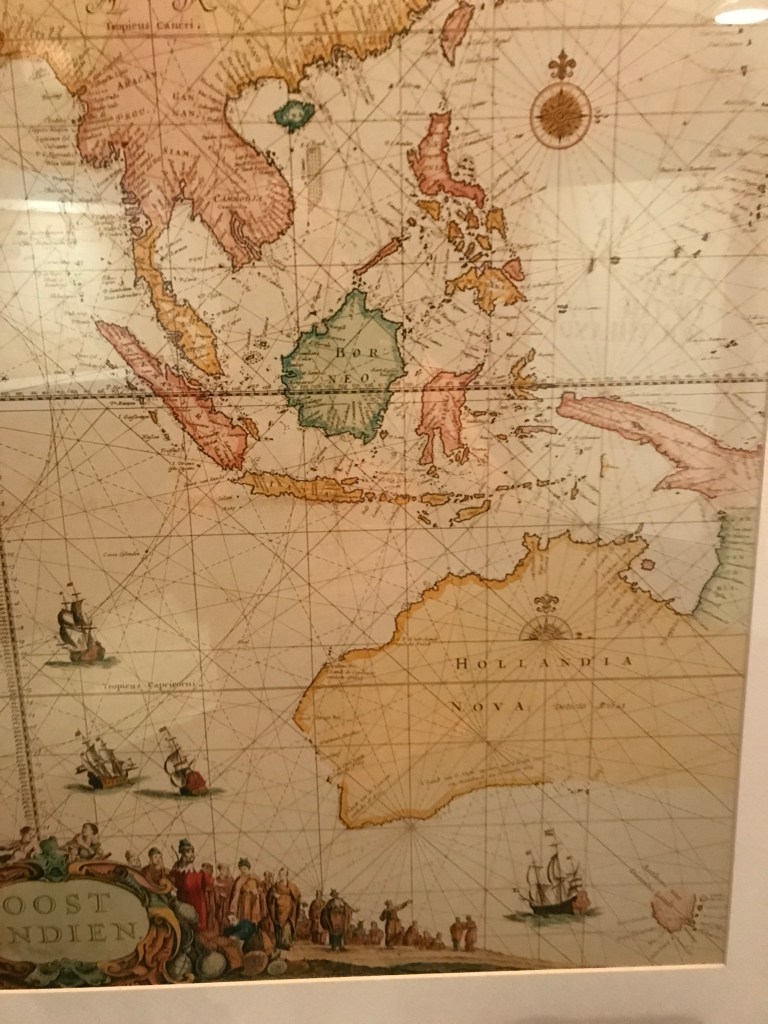

As a child growing up in Australia, I was taught the patently false information that the English mariner Captain James Cook ‘discovered’ Australia. (Recently, there was even a plan by our Federal government to further exaggerate this mistruth by circumnavigating the continent in a replica ship!) The continent was inhabited by Aboriginal people for some 60 to 100 thousand years before it was ‘discovered’ and of course there was lots of connections made by those in the north of the country to nearby parts of southeast Asia. In fact, Cook was not even (close to being) the first European to ‘discover’ Australia, as the museum makes clear in many ways. The Dutch East Indies (private) company – known as VOC – made landfall many times on the Western Australia coast, partly because navigation in those days was not as successful as it is today:

Over time, the western half (at least) of the Australian coastline was mapped fairly well by Dutch navigators, so that the following remarkable map of the East Indies by Pieter Goos that was available as early as 1660 (well over a century before Cook arrived). The ‘Great Southland’ aka ‘New Holland’ as well as most of Tasmania was well known to other Europeans long before the English arrived late in the eighteenth century. A good part of the map was the result of the work of the Dutch navigator Abel Tasman, after whom tasmania was later named.

The Museum had some interesting displays of various kinds about navigation – a much trickier prospect in the 17th century than it is today (when my smartphone uses its GPS much more efficiently than any printed maps.) Here are some of them:

Mathematics was a of course a major tool used by navigators, but the photo shows some other kinds of tools: an astrolabe (to determine the location of the sun, and thus help to locate the latitude of the observer), an hourglass (to measure time, from which boat speed could be measured) and some weights (used with an attached string to determine water depths). I continue to admire the early seafarers and map-makers using such tools so well, on small ships in difficult sea conditions – a tribute to their mathematics, of course. At this stage, navigation had not mastered the art of determining longitude efficiently, as this required a good chronometer, measuring time very accurately, which accounts for the regularity of ships running ashore and sinking … in fact, Captain Cook’s ship was one of the first to be testing better navigation methods using a chronometer, but that was long after the Dutch navigators had mapped much of Australia.

The Museum had several delightful models of early ships, including the Duyfken shown above, which was the first European ship to visit Australia (in 1606). These are painstakingly studied and constructed, and a delight to see. At the moment (for just a few more days) a replica of the Duyfken is actually moored in Fremantle, as the second photo shows. (More details are at https://www.duyfken.com) It is sailing away (forever!) in a few days from now, so I hope to see it more closely while there is still a chance. It continues to amaze me so that so many people could inhabit such a small vessel for so long and in such dangerous circumstances …

Leaving the Museum, it’s not hard to see the connection with the sea, which is a very short distance away. These days, of course, it is a much easier and safe matter to visit Fremantle than it was for the early seafarers, and the nearby shore is mostly used for recreation rather than for rescuing ships in trouble.

The nearby fishing boat harbour is still used for a small fishing fleet, but is known to many of us an area in which food and beverages are available in casual settings – most obviously various forms of seafood, including of course fish and chips.

The modern fishing industry was originally developed (I think) by mostly southern European migrants, and I love the sculptures recognising that past – one of which is shown here. I have eaten many times at Kailis’ outdoor eatery at the harbour, too, but usually had to fight hard to find a table (as well as fight hard to keep the seagulls at bay!). The Kailis family were of Greek origin and had a big influence on local fishing, as well as eating outlets like this one. Sadly, these days, the place is almost deserted, as the pandemic has kept tourists away and locals are busy at work. It feels strange to have so few people there, but it’s still a lovely place for lunch.

The early Italian influences on Fremantle are never very hard to find. A good example is Gino’s coffee shop, which has been here on a conspicuous corner for as long as I can remember, and long before it was fashionable to go out to have a cup of coffee with a friend. They still make great coffee, but the ‘cappuccino strip’ (as it came to be called) on which it is located is struggling these days from the effects of the pandemic, and the loss of tourist trade. It’s sad to see so many shops falling vacant, unable to survive … I hope that times will change before much longer.

Elsewhere in Freo, all kinds of reminders of other times are evident. Too many to document here, but here are just two examples. A lovely old wall (in fact, right behind Gino’s), with an artistry in bricks that is never seen these days and a delightful grocery with the most amazing smells; the Kakulas Sisters sell all sorts of bulk spices, coffees, teas, sweets, and many other things that make it a delight to wander around. (Click on the images to see more of them.)

By its nature, a port city like Fremantle is connected to cultures elsewhere. While the Italian and Greek roots are evident, and there is increasing recognition of local Aboriginal (Nyoongar) people, Fremantle has always had a multicultural feeling. Indeed, the whole of Australia is multicultural, with around 30% of us born overseas. So I enjoyed the sign below, drawing attention to who we are:

‘Meandering’ has an intrinsic sense of ‘slow pace’. Fremantle is still a lovely place to meander around, and has many more attractions than the few things mentioned here.

If you’re nearby, its certainly worth a day trip … when we are all allowed to travel again.