I had some misgivings about visiting San Gimignano, a famous medieval hill-town, mostly because of how famous it is. (The city is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site.) I was concerned that it would be overrun with tourists and that the town would be oriented to dealing with them – understandably of course. As it transpired, visiting in mid-winter mostly resolved that problem and so I enjoyed a couple of days there. The photo above was taken just as I was leaving, with gloriously irresistible evening sunlight on a corner of a city wall.

My visit was relaxed and I saw only one obvious and small group of tourists, following their tour leader’s flag, and I had no difficulty getting a seat at cafes and restaurants or moving around the city streets unimpeded or waiting in line for anything. (Click on the pictures for a better view).

As I have been doing for some weeks now, getting around on buses and trains has been easy and inexpensive, so my trip to San Gimignano from Lucca involved three trains (to Pisa, Empoli and Poggibonsi respectively) and then a bus for the last half hour. The trains are comfortable, clean and safe and I have had no trouble booking trips in advance on my phone (although ticket machines are easy too). Bus travel has been made easy by Tuscany buses all allowing a credit card instead of a ticket to be used enter and leave a bus, a process colloquially called Tip Tap; previously, one had to seek out a Tabachi (sort of like a tobacco shop) that was open to purchase tickets before entering the bus, and have minimal language capabilities, all of which was not always convenient, although it is still possible.

These days, more recent trains (like the one shown) have lots of handy recharging ports for phones and very good TV communications, announcing upcoming stops, advising transfer platforms, giving maps, schedules, transit updates, etc. It’s all much easier than it used to be, I’m sure.

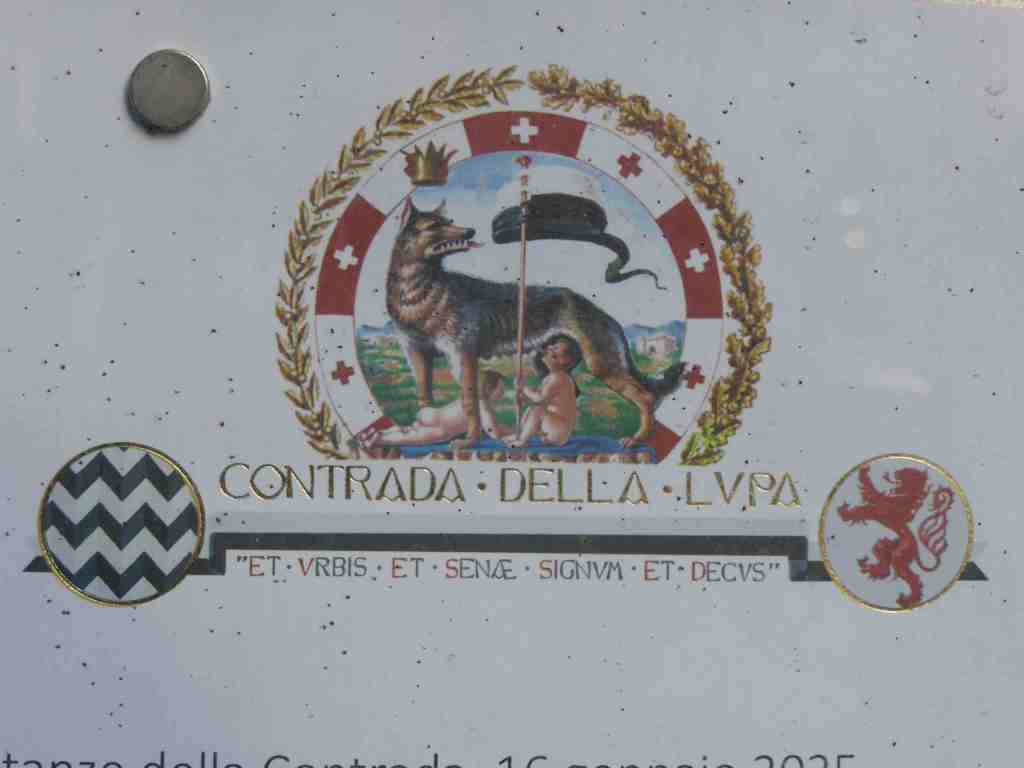

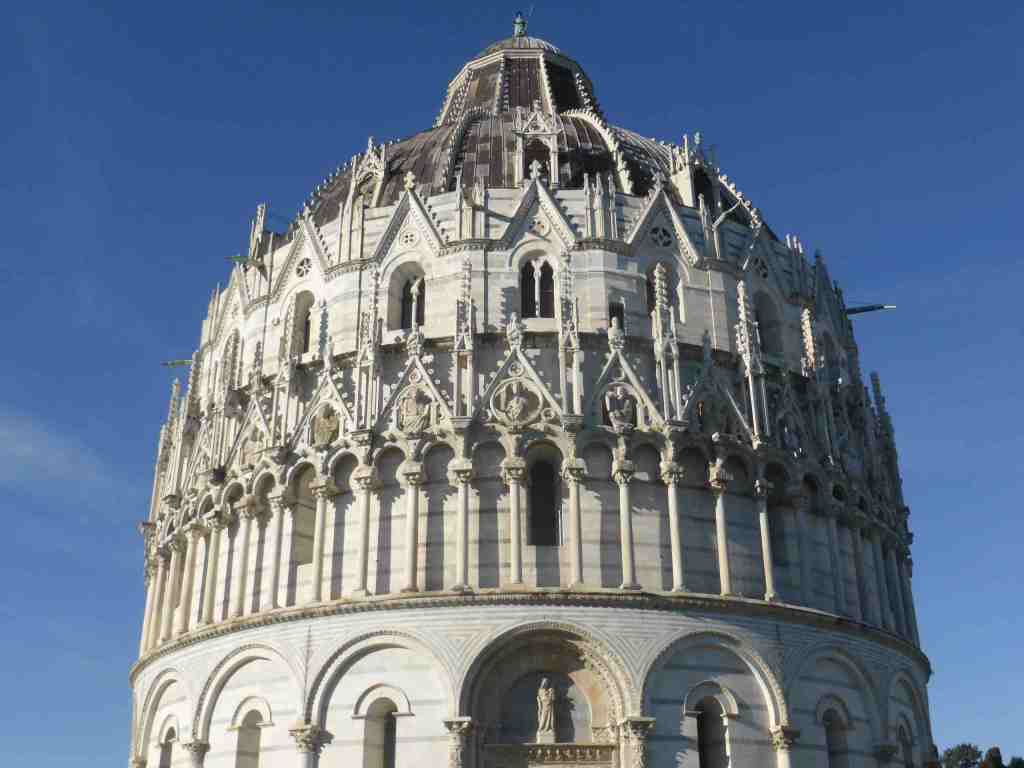

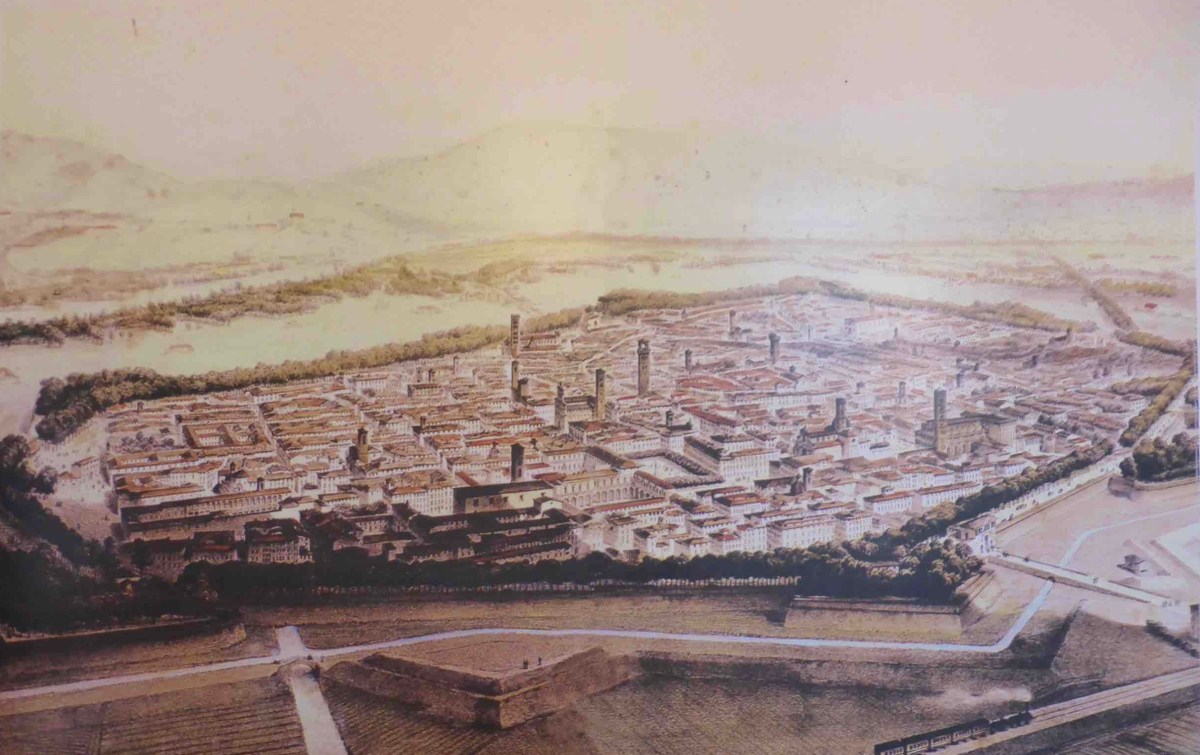

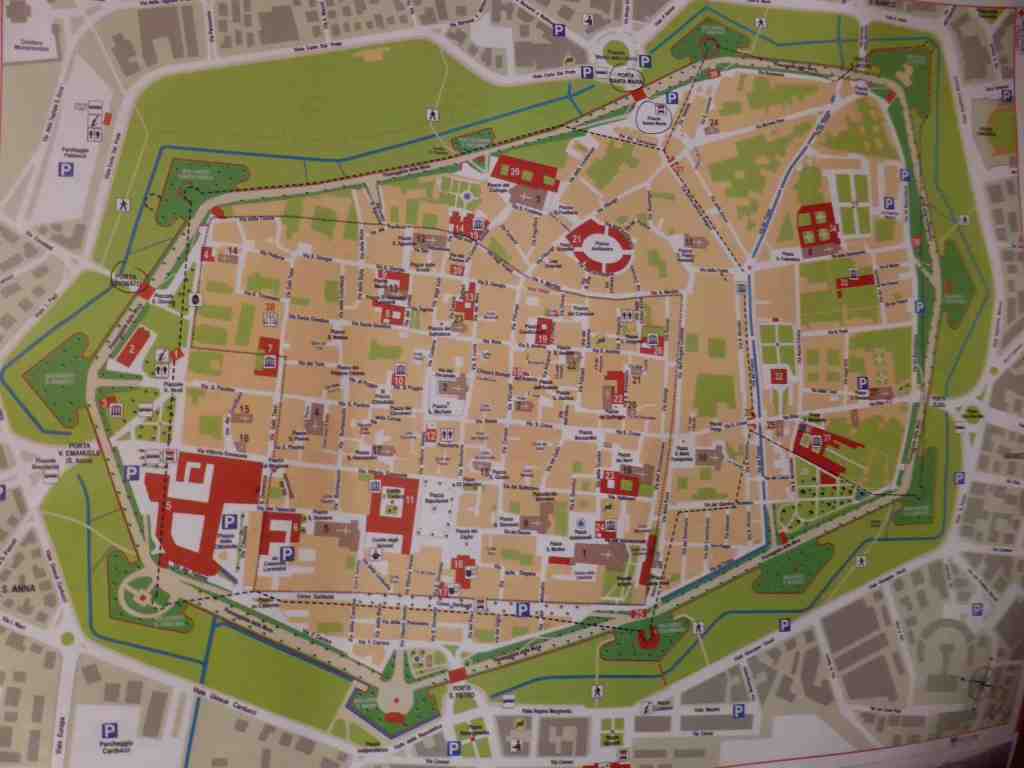

San Gimignano often appears in tourist brochures for Italy, with its distinctive feature being its towers. Seen from a distance, these do look impressive with the small city sitting on top of a Tuscan hill, but they were frankly not of much interest to me. There used to be 72 of them, but now there are only 14 left. As you can see from the snapshots below, the towers are large – but are not skyscrapers – and mostly don’t have many windows, so were probably not usually used as dwellings.

I had expected that the towers served some kind of military/surveillance purpose, but was surprised that they were more likely to be vanity projects, with richer people outdoing their neighbours in conspicuous displays of wealth and power. Of course, climbing the towers will give a good view of the city and the (lovely!) surrounding countryside, so they could have strategic uses as well as bragging rights. I climbed the tallest tower, the so-called Great Tower, built in 1311 and soaring up to 54 m high.

The views from the tower make it clear that almost all buildings in San Gimignano are built from stone and bricks and almost all roofs use the same terracotta tiling. All the streets are paved with stone, bricks or tiling, which gives the city a distinctive feel.

Looking beyond the city, the rolling fields below show a variety of agricultural pursuits, especially growing wine and olive oil. You can also see nearby and more distant settlements of various kinds, looking from towers or otherwise. It was poor weather for visibility (or photography) – the downside of winter – so I know these snapshots don’t do justice to the scenes, but at least they might give an idea of the ambience.

Many shops and most restaurants were closed for the holidays (that is, the times when the tourists have not overrun the city), but the few that were still open gave a hint of what was normally available. I assumed that local people don’t eat out much – as restaurants are mostly for tourists, unfortunately. There were of course obvious tourist shops selling souvenirs of the usual kinds (many, but not all, made in China), but there were also some shops displaying lovely local crafts and produce (especially wine and oil). Some of the things looked lovely, but I’m not really here for shopping. The boar picture below is an example of attracting the attention of tourists (well, I took a photo … so it works!), and I noticed wild boar on several restaurant menus too.

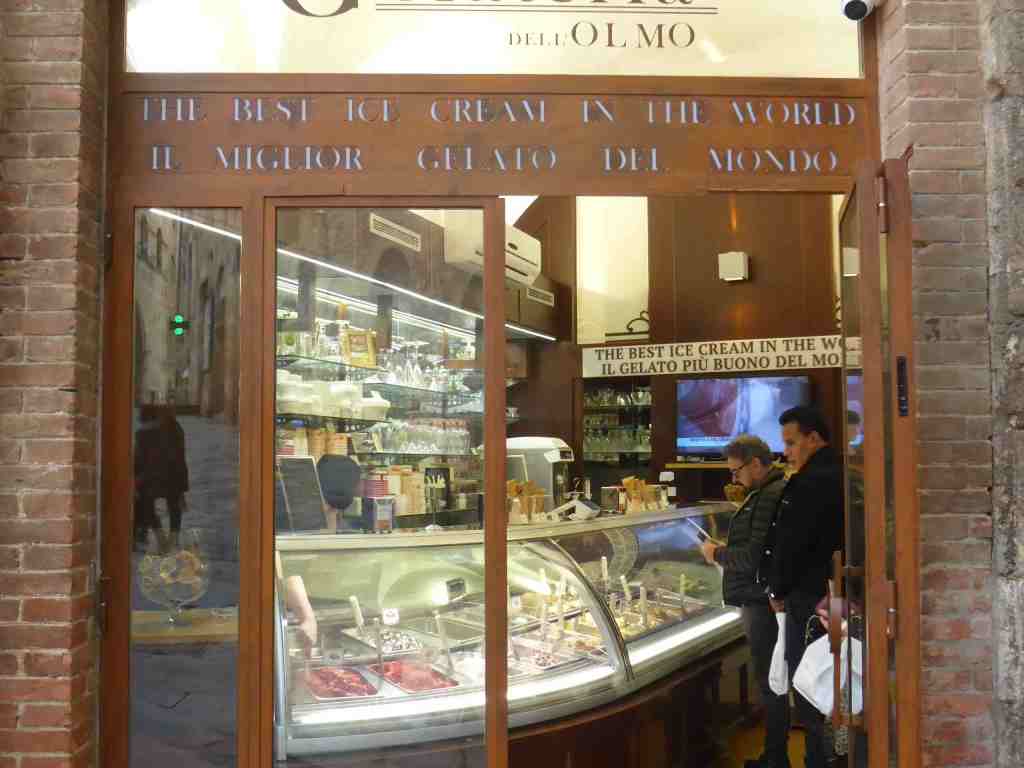

Of course, there were gelaterria (ice cream shops), including two in the main square, which each claimed to be the best: it’s Italy after all, and the ice cream is wonderful. I tasted them both, naturally, on different days. Each was excellent.

Wandering around town, which was relatively easy as it is quite small and uncongested, gives a good sense of what a medieval hill-town was probably like, with vey few horizontal streets, lots of stonework and brickwork and lots of picturesque views. Here are a few of the many pictures that caught my eye in the main street, pleased that the town was not bursting with tourists as it apparently is in the warmer months. Many buildings go back to the 12th and 13th centuries.

Many smaller side-streets have lots of steps, and many walls everywhere in the city have extraordinary patchworks of stones, marble, rocks, bricks, etc, probably accumulated over a millennium or so.

I also noticed a distinctive pride in front doors, which I guess is people’s main way these days to display their standing (as tower-building seems to have gone out of fashion). Here’s a few examples, the first of which was the door to my own abode (I spent a night in the city).

It’s one thing to visit a medieval hill-town, but another altogether to live in one, I suspect. Two things I noticed were that the streets were spectacularly clean (I have noticed this elsewhere in smaller Italian towns and cities too). I expect that the lack of tourists at present is a help, which must reduce litter. But I also noticed lots of street-sweeping machines and people, making sure that the city was very clean. I also noticed lots of small three-wheel delivery trucks, which I’m sure are used for a lot of tasks (including taking tourist luggage around in high season – as most streets do not allow cars to stay – they are parked outside the city walls); some of these little trucks seemed to struggle getting up the hills, as I did myself at times.

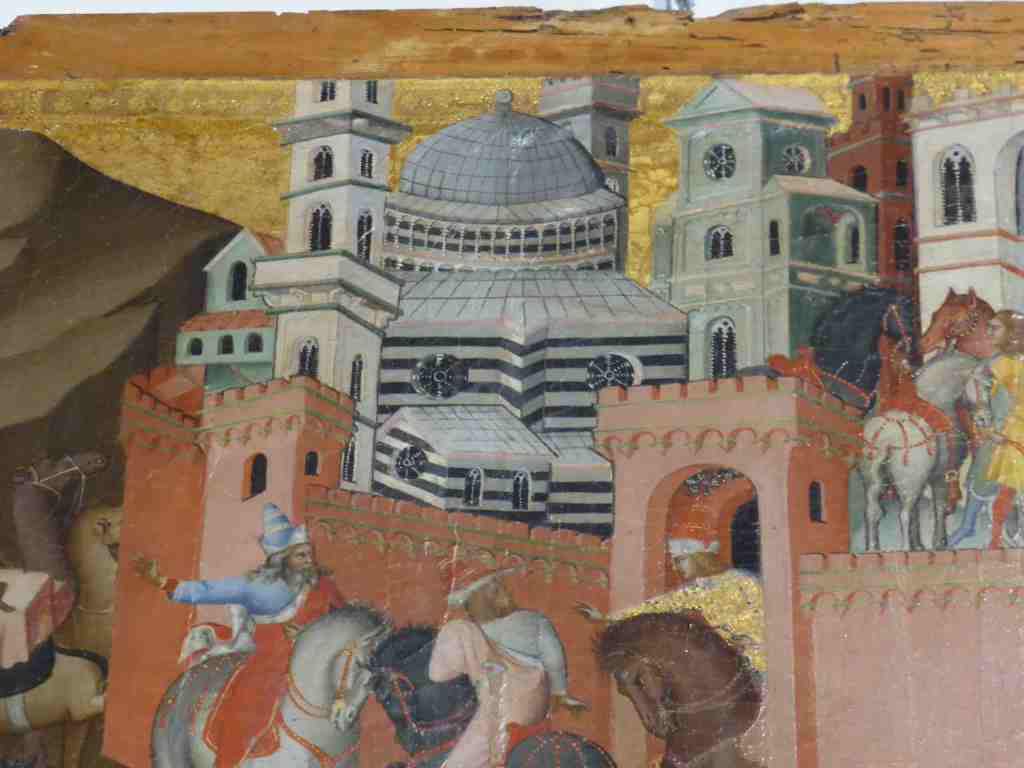

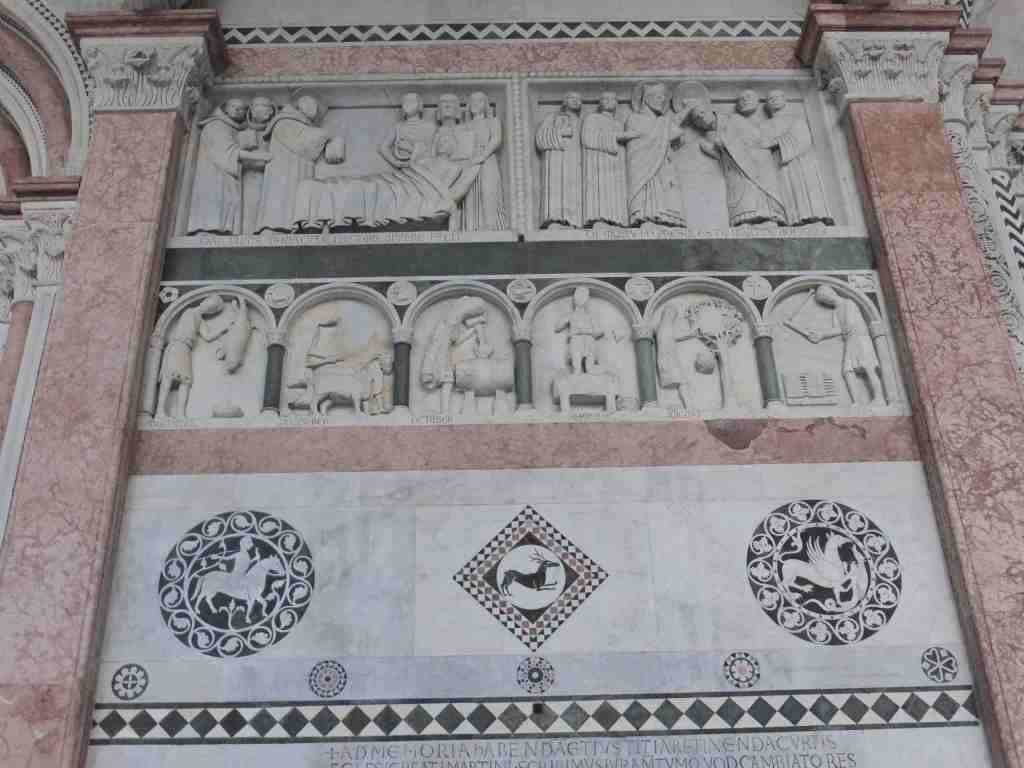

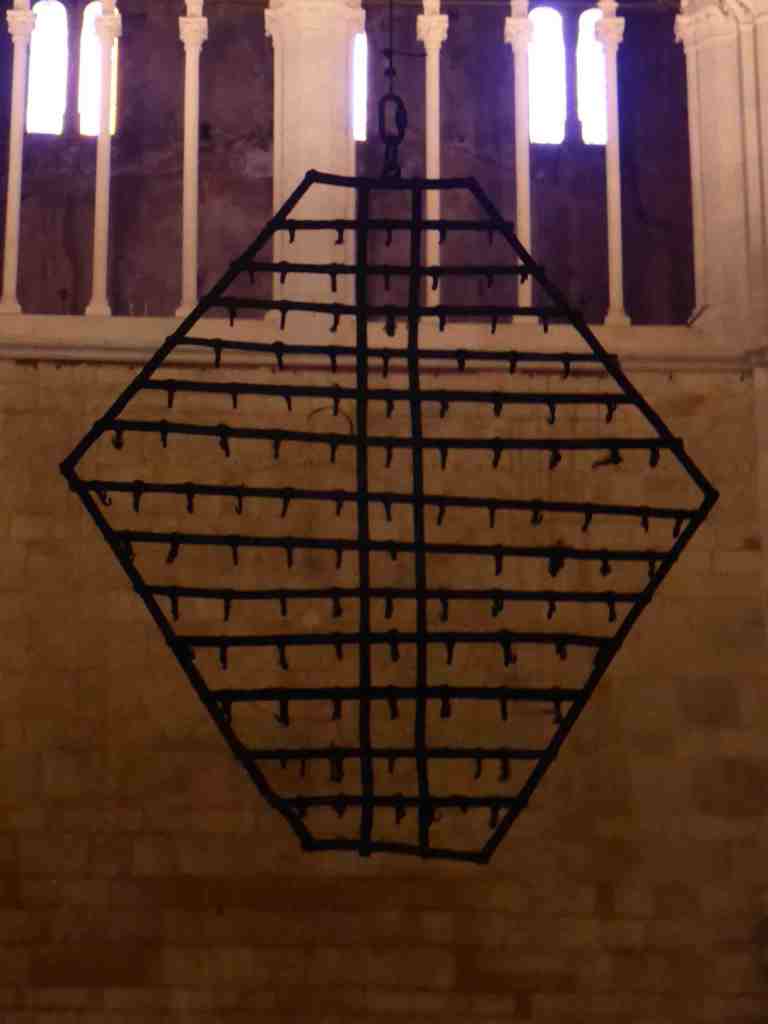

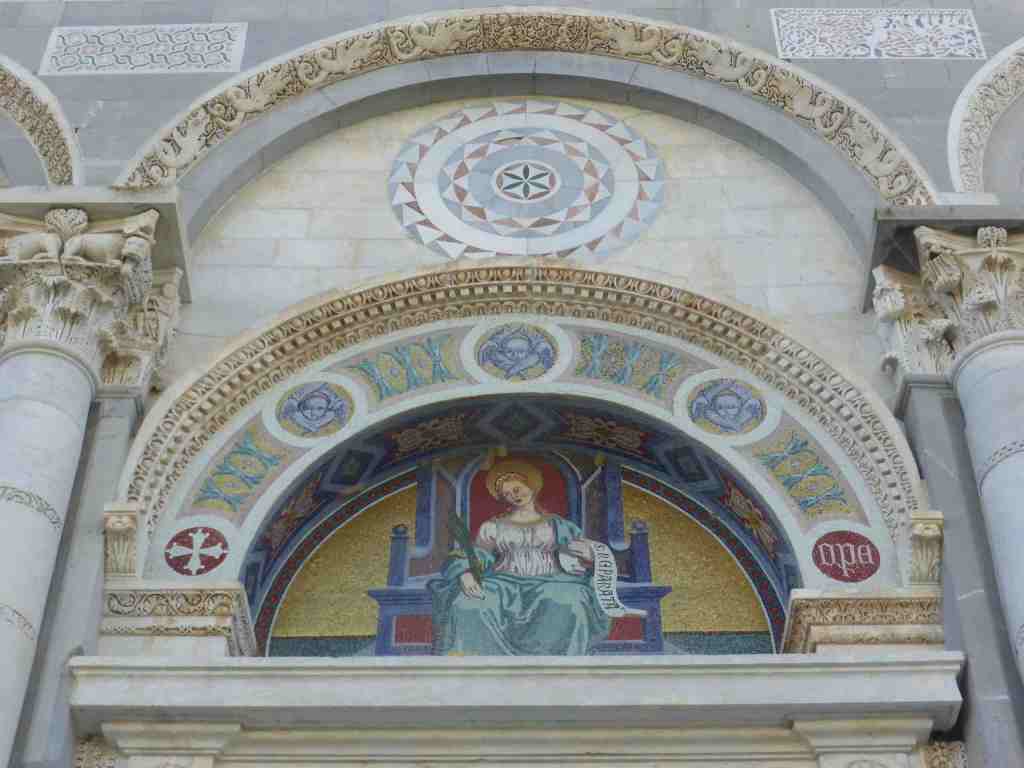

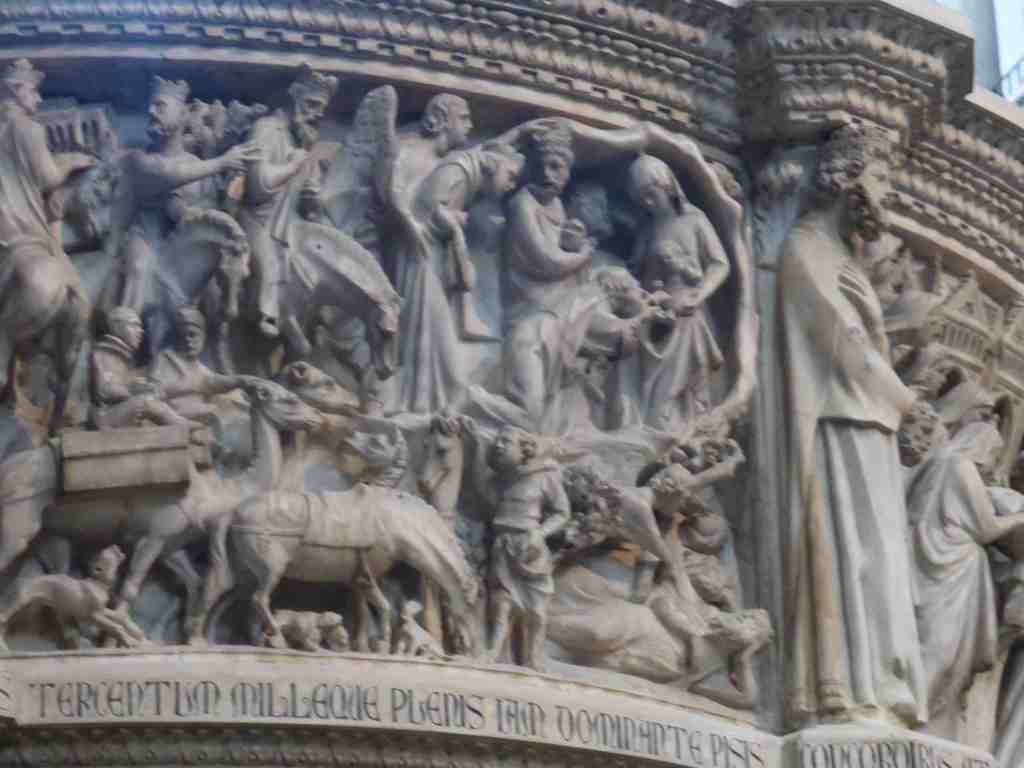

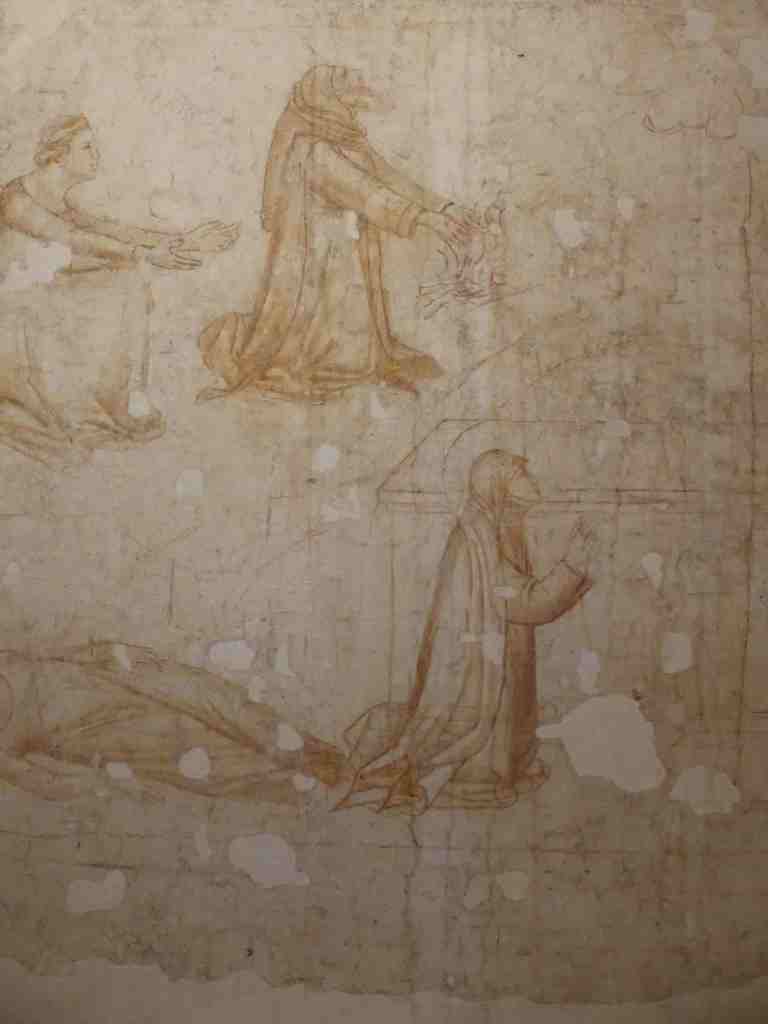

Apart from the general ambience, I found the medieval cultures of San Gimignano of most interest. There are a number of quite spectacular frescoes in various buildings from about the 13th century, including churches, the town hall and elsewhere.

Frescoes were a common form of representing images as the walls were already available and they were likely to endure (as some have for many hundreds of years). They needed to be painted when the wall plaster was still fresh (hence, ‘fresco’) and required great skill. Many (but not all) are religious in focus, which no doubt helped a mostly illiterate population to understand their religious stories and to recognise saints and significant people. (E.g., St Peter, below, has the key …)

Several frescoes showed non-religious scenes, such as the husband and wife enjoying a hot tub together, and some showed graphic scenes from Dante’s Divine Comedy, showing the gruesome punishments of eternal damnation in hell, serving a dire warning.

Dante in fact was a prominent visitor to San Gimignano in 1299, as an ambassador from nearby Florence, and he was recently celebrated in 2021, the 700th anniversary of his death. He is revered in Italy – rightly so – as the poet who championed the use of the vernacular language, when it was assumed that Latin would be used for everything, even if the people couldn’t understand it. (Older notices in churches are still in Latin, it seemed to me.) As an aside, it is noteworthy that the two possibilities for Italy to mint €2 and €1 coins are taken with a medieval poet (Dante) and a Renaissance artist/engineer/scientist (Leonardo da Vinci). I think this is much nicer than having politicians or monarchs on coins.

The pictures show a bust of Dante from the town hall, his head on the €2 coin and Leonardo’s wonderful Vitruvian Man on the €1 coin. [Each EU country can make its own coins, which are then used in all EU countries, so this is how Italy represents itself to others.]

The wonderful mathematics of the Vitruvian Man is described on Wikipedia with: “The length of the outspread arms is equal to the height of the man. From the hairline to the bottom of the chin is one-tenth of the height of the man. From below the chin to the top of the head is one-eighth of the height of the man. From above the chest to the top of the head is one-sixth of the height of the man. From above the chest to the hairline is one-seventh of the height of a man. From the chest to the head is a quarter of the height of the man. The maximum width of the shoulders contains a quarter of the man. From the elbow to the tip of the hand is a quarter of the height of a man; the distance from the elbow to the armpit is one-eighth of the height of the man; the length of the hand is one-tenth of the man. The virile member is at the half height of the man. The foot is one-seventh of the man. From below the foot to below the knee is a quarter of the man. From below the knee to the root of the member is a quarter of the man. The distances from the chin to the nose and the hairline and the eyebrows are equal to the ears and one-third of the face”. But I (seriously) digress …

I also visited an interesting archeological museum in San Gimignano, showing some of the early history of the area from the last 2500 years or so. I liked the lovely Etruscan statue below from the third century BC and was also impressed at the constructions of a villa, showing the mathematical characteristics of the designs. I am always amazed at the ability of archeologists to understand so much from just a few fragments, such as the glass decorations of various fish objects from prehistoric times.

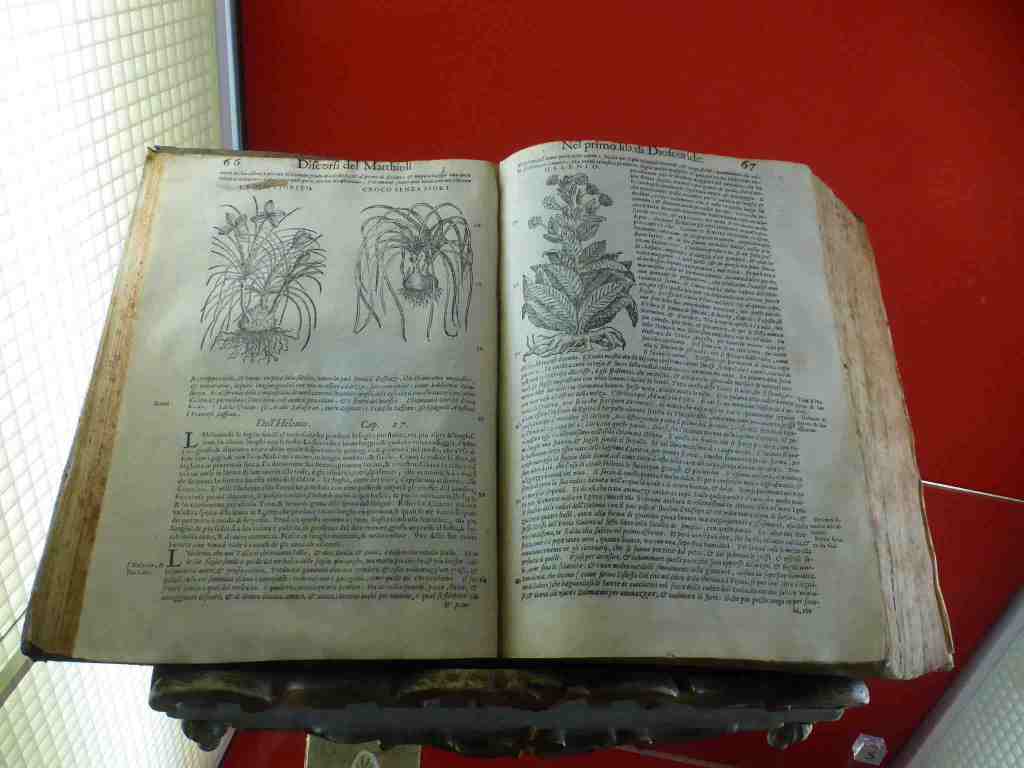

Similarly, the early days of pharmacy were on display with the details of a medieval speziera, essentially a 14th century pharmacy, with lots of use of herbs and chemicals, as well as lovely ceramics from the past.

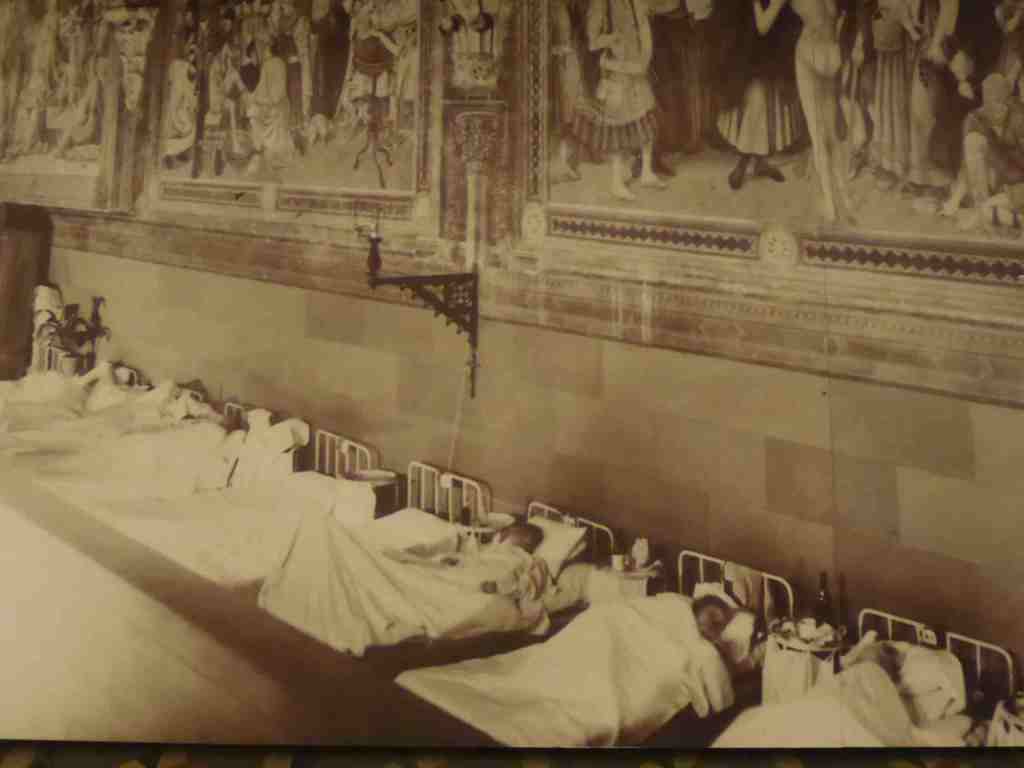

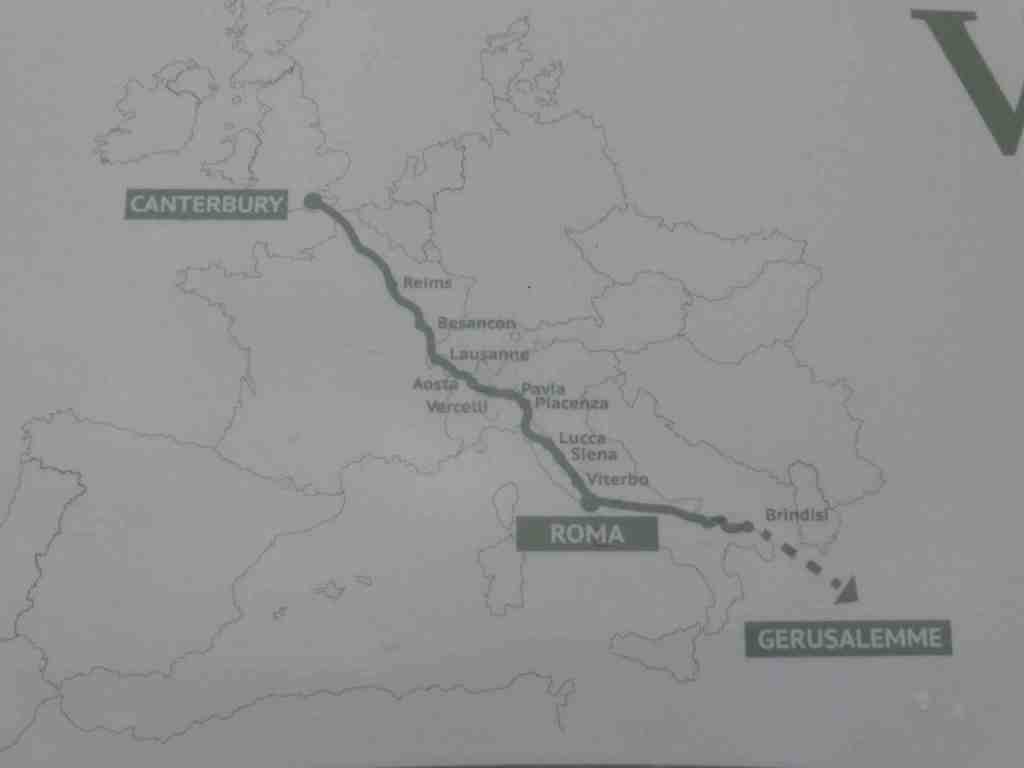

San Gimignano became prominent in the early medieval years as it was on the Via Francigena, an ancient pilgrim’s trail from Canterbury, England, to Rome and then Jerusalem (although I was surprised to see the map showing Lucca and Siena, but not San Gimignano in between them). The trail is still evident in the city, with lots of markers for pilgrims, and I even found in a museum the traditional shell representing pilgrims. (Also used on the Camino di Santiago in Spain, I believe.) Hence the need for a pharmacy and hospitals to look after travellers in medieval times.

San Gimignano would have become and remained more prosperous had it not been for the Black Death (the bubonic plague) in 1348, which wiped out literally half of the population (as for nearby Siena) and from which it never really recovered. Being on the Via Francigena probably didn’t help the infectious disease progress, I assume.

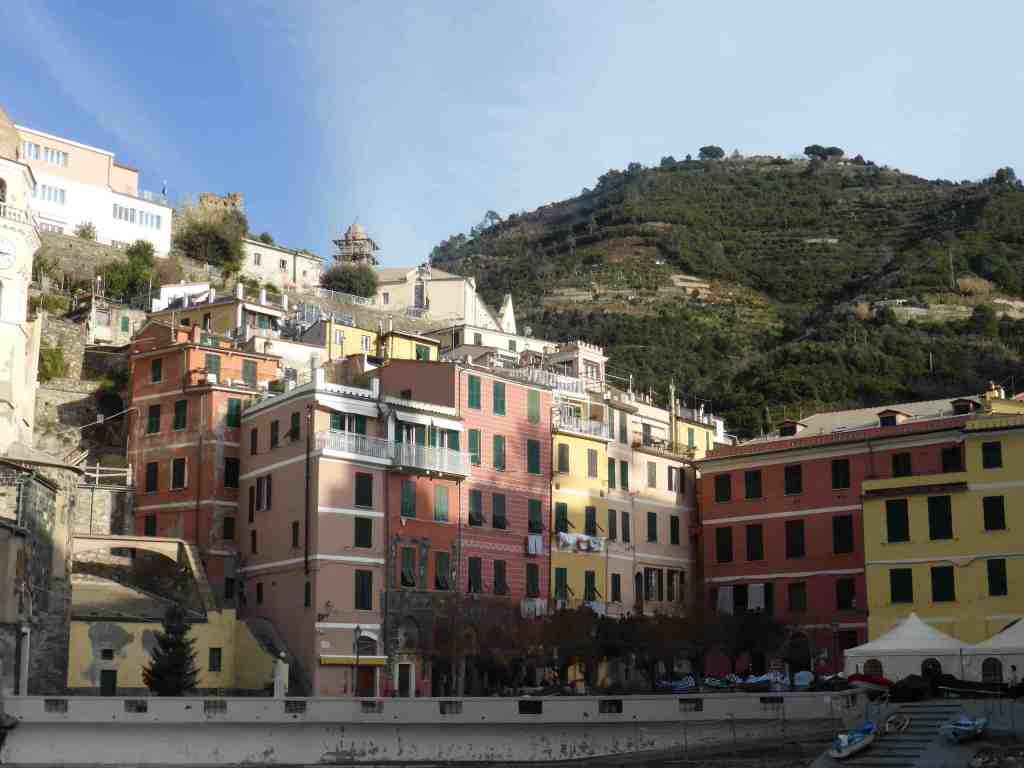

The visitors have now returned in the form of tourists instead of pilgrims, restoring the city’s prosperity. So I was pleased to be there when the number of fellow tourists was so low, and I enjoyed much more about this lovely medieval city than its famed towers. I have seen tours advertised to ‘see’ Pisa, Siena and San Gimignano in a single day, and was really pleased that circumstances allowed me to have much more relaxed visit than such a tour would provide and to hopefully see a lot more.

San Gimignano is certainly worth a visit, especially if you can do so when others are not visiting and you get to see the sun go down at least once while you’re there.