It seems somehow unfair to think of a place entirely because of an engineering error more than 800 years ago, but such is the fate of Pisa. As a child, I learned about the “Leaning Tower of Pisa” (without at first really knowing whether Pisa was a place or a person) and of course the tower alone has put Pisa on the map – and certainly on the tourist trail. So I popped down for the day from Lucca to check it out – a short train ride of about 25 minutes; that’s a bit less than Perth to Fremantle by train. The most interesting parts of the city, including the tower, are on the so-called Field of Miracles shown above. Of course, this is all a World Heritage Site: the Piazza del Duomo, as it also called, was added to the List as one of the first Italian sites to be given that recognition.

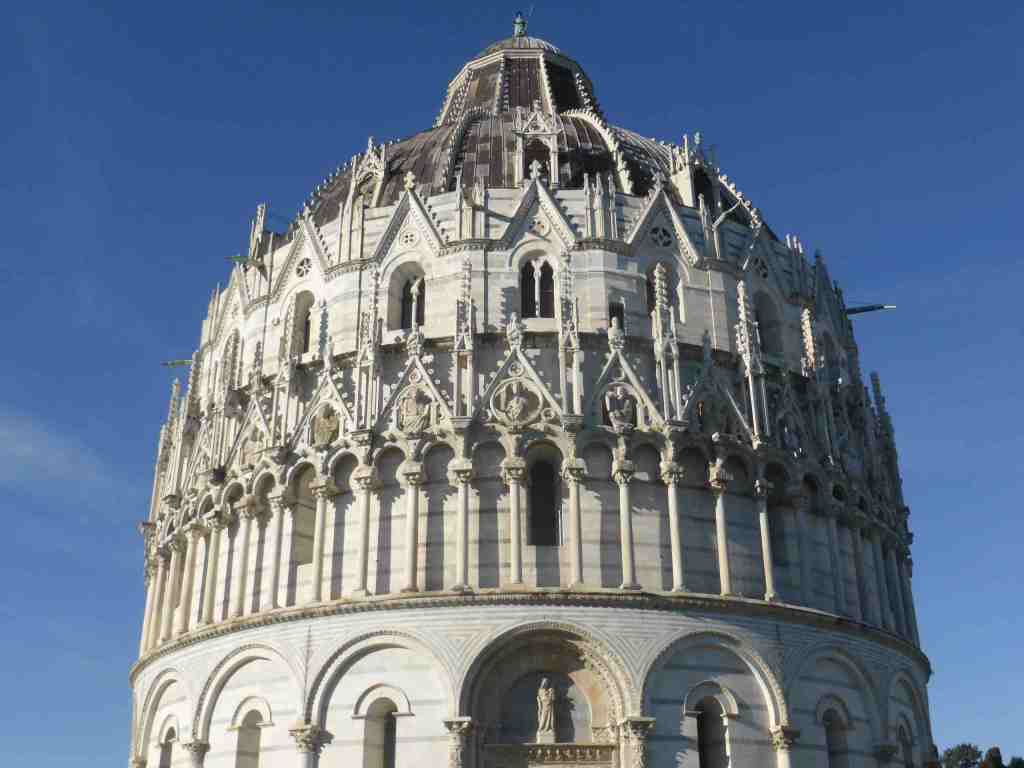

I chose to visit the Baptistery first. It’s a massive building – the largest baptistery in Italy, with a circumference of 107 m. It’s also tilted a bit, but not nearly as much as the tower … it’s not easy to take a photo anywhere on this Field that doesn’t have a tilt of some sort!

It seems to me excessive to have such a large building solely to baptise infants … many Australian churches make do with a small bowl of a metre across, or even smaller. But such are customs, and I know other baptisteries here (such as that in Florence) are famous too. It is a magnificent marble structure externally, and gleamed in the sunlight with decorative carvings. Inside was less ornate but still very beautiful and I didn’t even spot the bowl used for baptisms. Every now and then, one of the staff made some nice sounds to show off the wonderful reverberations.

The cathedral or Duomo shown above is also spectacular, both inside and outside. Unlike its neighbours, it’s actually vertical: two of the photos above show the lean of the tower behind it.

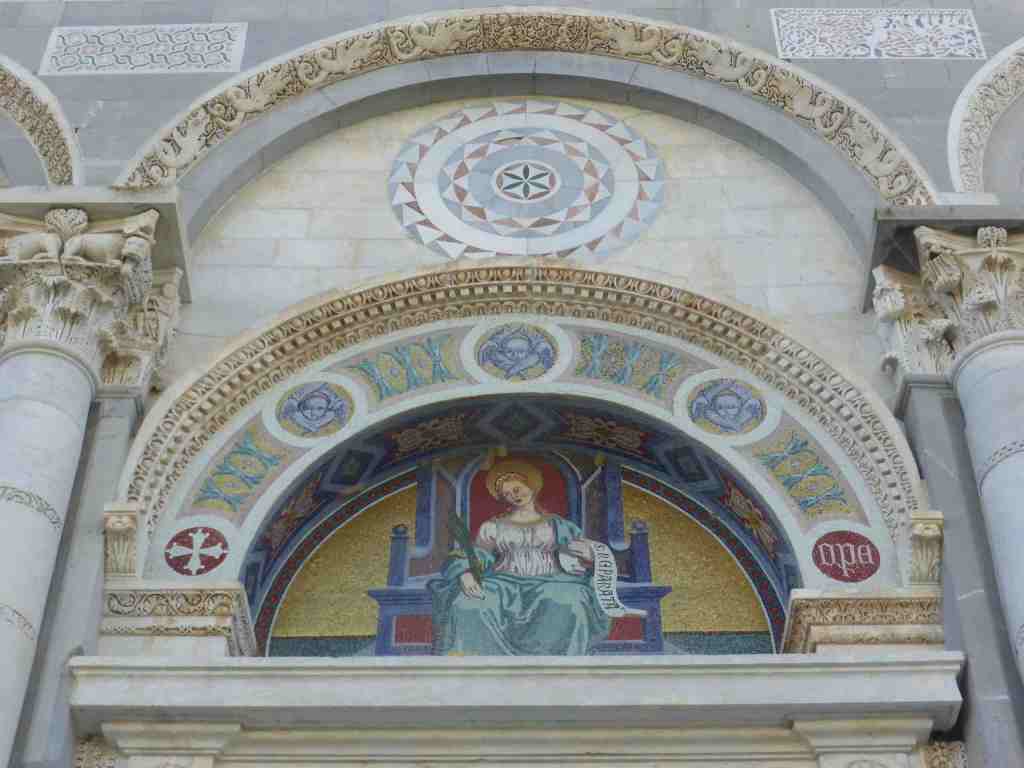

As you can see, the building has enormous doors, much larger than necessary to fit normal people through. I assume this is an artistic statement of some sort – and have seen lots of large doors in Lucca as well, both on churches and on other buildings. Maybe also the doors have to sometimes accommodate large poles in processions too? The craftsmanship looks lovely from a distance, but – as the closer-up photo of the top of a door above shows – there are lots of very fine details if you look closely enough. As well as religious iconography of various kinds, I was interested to see traces of Islamic art as well – more of that later.

Inside the cathedral is spectacular too, richly adorned with religious decorations of various kinds. Again, the closer you look, the more detailed artistic work is evident from floor to richly decorative ceiling. I could see a second floor, shown above, but could not see how to get there. This cathedral would be noteworthy even if it did not have a vertically-challenged bell tower.

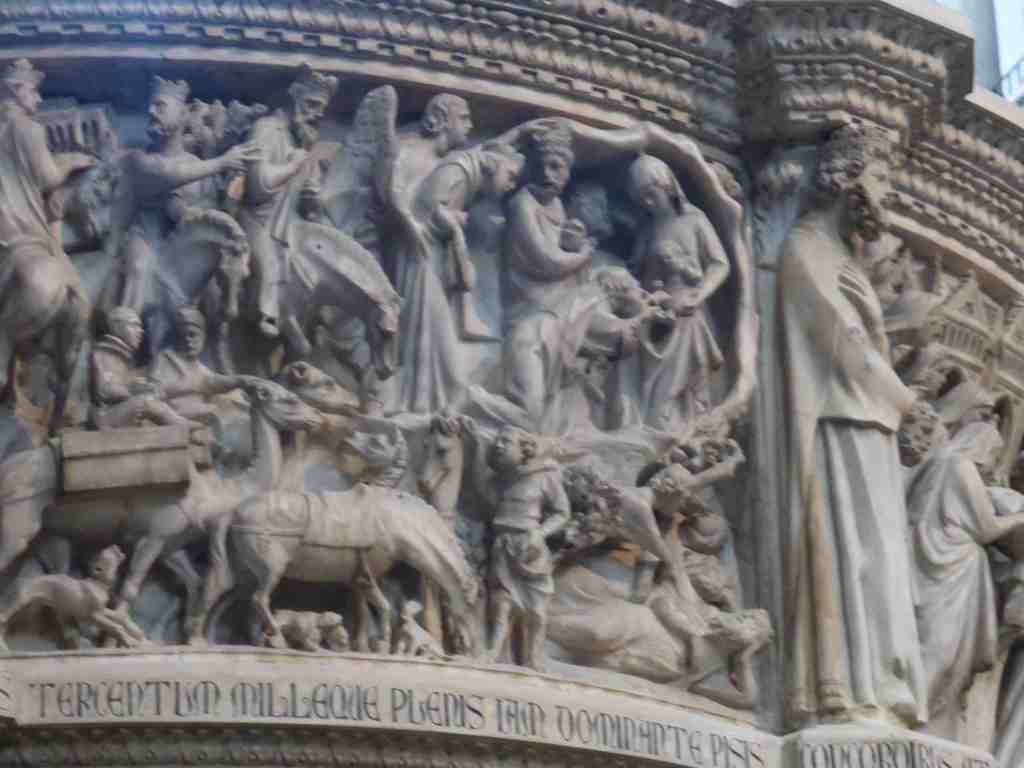

There were too many details to record here, but the pulpit is especially noteworthy. Shown below, it has an array of fine gothic carvings, and extraordinary ‘legs’ holding it up, all made by local craftsmen/artists around a thousand years ago.

What is not shown anywhere (unless I missed it) is any recognition that this is the very place where Galileo Galilei watching a swinging chandelier and hence discovered the law of the pendulum – that the time taken to go from side to side depends only on the length of the string, not on the weight on it or on the angle from which it has been released, and thus that the force of gravity on Earth does not depend on the wight of objects. This observation eventually lead to the invention of timepieces that relied on the physics the medical student Galileo had observed in the 16th century. Grandfather clocks rely on the physics that he discovered sitting in this church. Galileo was born in Pisa and studied medicine at the local University of Pisa, one of Europe’s first universities, founded in 1343. (He switched from medicine to natural sciences and was appointed professor of mathematics at the university shortly afterwards; long regarded as one of the first scientists, he later struggled with the church’s doctrines and opposition to scientific results.)

But I digress … the next notable building of course is the famous bell tower, the so-called leaning tower of Pisa. These days, more careful soil-testing ensures that buildings stay vertical, but this one has been leaning since construction began in 1173. It is a magnificent building in gleaming marble and would be revered even if it were vertical, I think.

It’s one of the best tourist magnets on the planet, and there is usually a swarm of them climbing it or being photographed in front of it, pretending to hold it up. I managed to resist both of these temptations, but did try to photograph it, mostly unsuccessfully. The angle of ‘lean’ depends on where you stand, of course … and is easiest to see if there is something vertical nearby. A couple of my more successful attempts are below, but even these do not capture the alarming lean that seems clearly visible when you stand next to it.

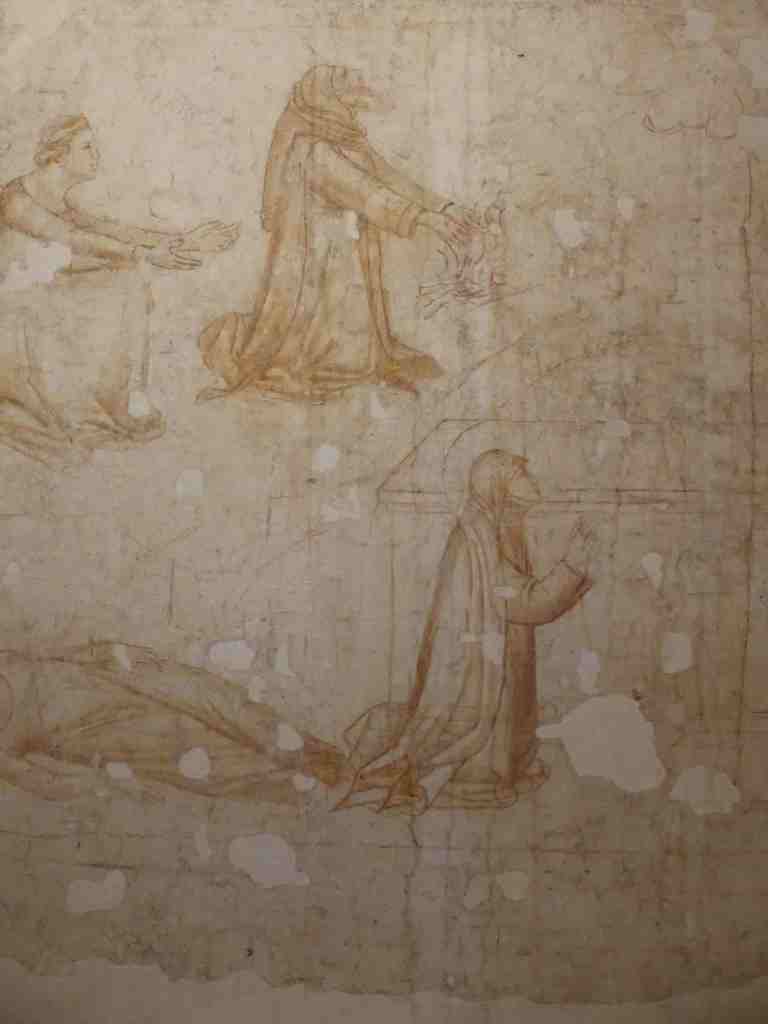

The other major ‘miracle’ on the field in Pisa is the Camposanto, a very large marble cemetery that was used to bury prominent citizens for about 700 years, many of them using recycled Roman sarcophagi. The walls were covered in magnificent frescoes in medieval times. But, sadly, the building contents and the frescoes suffered badly under Allied bombing in 1944 after the roof caught fire and collapsed; many statues and sarcophogi were destroyed, as were most of the frescoes, so what is left is fragmentary.

The picture above also shows some of the chains that were once used to protect Pisa’s harbour in the days when medieval Pisa was an important naval power, and not just a city in Italy. Pisa and Florence were medieval rivals, but Florence got the upper hand around the fifteenth century, I think; nowadays they are no longer city-states, but Italian cities.

I was quite excited to find that one of the relatively few surviving statues was that of Fibonacci, placed in the Camposanto in the 19th century, although he lived back in the 12th century, around the time that the cathedral and other buildings were being constructed. He also lived before the founding of the University. (He is sometimes referred to as Leonardo di Pisa) Although many associate him these days with Fibonacci Numbers (1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, …) where each term in the sequence is the sum of the previous two, his biggest achievement was probably popularising the base 10 Hindu-Arabic number system that we use today (i.e., 1, 2, 3, 4, …) through his publication in 1202 of a book Liber Abaci (Book of Calculation), persuading the base-10 number system to be used instead of more cumbersome methods, such as Roman numbers.

I had known (but somehow I had forgotten!) that Pisa was the home of both Galileo and Fibonacci! Wow!! Here is his statue:

The tragedy of the fires in the Camposanto have lead to an extraordinary art restoration attempt on the site nearby, where the drawings underneath the ruined frescoes are being gradually restored and the work is on public display in a large building on the Field. Here is a small example, as well as one of the restored frescoes in the Camposanto itself:

There are lots of works of art from the Duomo that are stored in an adjacent museum, which is surprisingly large (given that the Duomo is not without art treasures in it.) I noticed in parts of the Duomo and elsewhere what seemed to be influences of Islamic art traditions, with characteristic mathematical patterns, presumably a consequence of Pisa’s naval (and thus international) influence early in the millennium. Below are a few examples, which I enjoyed seeing. (The first of these was on the floor of the Baptistery, not in the Duomo).

The rest of Pisa was pretty unexciting after all that, unsurprisingly. I wandered back to the train station, crossing the River Arno along the way – the same river that runs (famously) through Florence, reminding me that the two cities are actually quite close to each other. (In fact, they are about the same distance apart as Perth and Mandurah, so that it is quite common for tourists in Florence to take a day trip to Pisa.)

I also passed a statue in honour of Italy’s first King, Vittorio Emanuele II, after the country was unified late in the nineteenth century. These reminded me that modern Italy is no longer a set of warring city-states, like Florence and Pisa at opposite ends of a river, but a (sort-of) unified nation.

So, yes, it was good to see the leaning tower of Pisa again, but there’s much more to the story than a piece of faulty engineering.