I needed some greens, particularly some celery and some spinach – it’s minestrone weather. I normally shop at my local IGA supermarket, a short walk from home, although some say it’s more expensive than the larger chains. Just for a change, as I sometimes do, I drove to a nearby Woolworths supermarket, as they advertise themselves as “The Fresh Food People”.

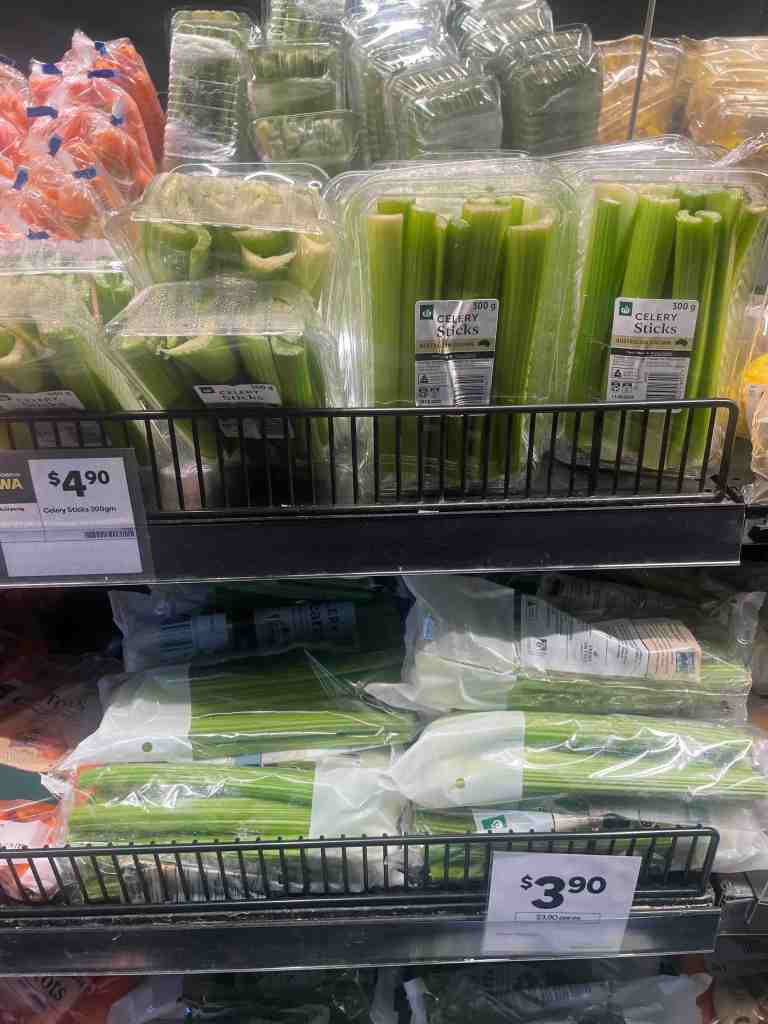

I found the celery, but had to make some choices, as you can see:

I was curious as to which of these was the best deal. Although I wanted only a few sticks, I was happy to buy a few more than I needed. Are they all of equivalent value? How do they differ?

The top one was the easiest, as it was a clear weight (300 g). It comprised only sticks, which someone had trimmed from a bunch, I assume; it must have been tricky to get exactly 300 g, I thought, but I guess the trimmer got skilled at this after a while. I could use these directly, without trimming them any further myself. But $4.90 seemed expensive; maybe that’s why people are talking about the high cost of groceries these days? I suppose I had to pay for the plastic container, too – although I already have too many plastic containers.

Mental arithmetic is sometimes helpful, and I checked that this put the celery sticks at about $16 per kg. (I noticed only later that the small print on the label confirmed the celery sticks were $16.33 per kg.)

The packets of sticks below seemed to be the same to me – only a little cheaper at $3.90. Then I looked more carefully and saw that they were described as Celery Hearts. That is, they were sticks but still had the bottom bit of the celery bunch intact, so I would have to remove it myself. That seemed like a good deal (saving $1) for not much effort, but were they the same size? No weight was showing.

I grabbed a couple of bags and took them to a scale to check the weight. Unlike the results of the well-trained and careful celery trimmers that made the 300 g packs, they were all quite different weights – to my mild surprise. I checked five of them at random and got the weights of 480 g, 515 g, 540 g, 525 g and 440 g. The variation surprised me – as if nobody was trying to make them all the same. The average (mean) weight seemed to be about 500 g, so I estimated that these cost a bit under $8 per kg, about half the price of the sticks, although some of them would need to be discarded to just get the sticks. That’s a big difference.

The final choice was a whole bunch of celery, as shown at the top of this page. They looked like a pretty good buy, even though they would need a bit of trimming – topping and tailing essentially. I mentally assumed they were the best buy and put one in my bag to take home. When I got home, I trimmed off the tops and weighed my bunch (including the bottom bit) and found that it was just over one kilogram. So it was about half the price of the heart sticks (which were about half the price off the sticks).

$16 per kg, or $8 per kg or $4 per kg is not much of a contest, even if there is a minute or so of work needed to trim them when I got home, especially if someone were concerned about food prices. I wondered whether other shoppers realised how different the various options were on their pocket.

I wanted to buy some spinach too, but The Fresh Food People only provided it in plastic bags (not loose), which felt like a slight contradiction of their title. So I headed homewards to my IGA to do that.

When I went to the shop I noticed that the celery bunches were also $4 each – the same price as they were at the supermarket that people said was more expensive. They also had another option – buying celery sticks in smaller quantities (one at a time). This time, the price was $10 per kg, a lot cheaper than The Fresh Food People’s $16.33 per kg, which required me to buy 300 g, rather than just a few sticks.

Again, I had a choice of ways to buy spinach at the IGA. I could either buy a plastic bagful (as at Woolworths) or I could buy my own preferred quantity (and I wanted only a decent handful):

The plastic bagful wouldn’t suit me – it’s always too much or too little – but it always seems much more expensive than the bulk product. The small print on the label meant that I didn’t need to do too much mental arithmetic (although I confess I had done it before I saw the small print!) At $2.49 for a bag of 60 g, the spinach is described as $4.15 per 100 g, and thus $41.50 per kg. I guess they use the small unit of 100 g for comparison shopping as nobody at home is likely to buy a kilogram of spinach (except Popeye, maybe?) .

In contrast, the bulk spinach is a bit less than half that price, showing as $19.99 per kg (suggesting – bravely – that someone might want to buy it in large quantities?) But, as in Woolworths, the huge difference in price is fairly easy to see, but I wonder how many people look for, or see, it.

I don’t doubt that groceries are costing us all more than we would like, and of course that becomes even more significant for people feeding a family, not just one person. But I wonder how carefully people choose their shops (based on their advertising or on popular opinion and hearsay) and how carefully they make choices amongst what is offered to them? I was not surprised that products are at different prices (something has to pay for the labour and the packaging and the advertising), but I was surprised at the scale of the differences.

Are you?